There are perhaps only three contemporary Swedish authors of the highest caliber who have reached the wider world: the poets Gunnar Ekelöf and Tomas Tranströmer, and Stig Dagerman, who in spite of his death at 31 lives on in new editions and research, especially in France where he is considered a Nordic existentialist in the tradition of Camus. This philosophy aside – rife during the 1940s and 50s – Dagerman ploughs the deepest grooves of existence. And it is from this chasm of dark poetry that he has been held up as a role model for our time.

Literary Nobel Laureate JMG Le Clézio speaks of Dagerman’s iconoclasm, his wild imagination and self-destructive humor, his mixture of curse and despair. Concluding his preface to Island of the Doomed, Le Clézio writes: “With humble gratitude to Stig Dagerman who consumed by his own fire showed us the way.“

Dagerman’ essay Our Need for Consolation Is Insatiable was separately published in France and has been reprinted for decades. In France, of Swedish classics, only Strindberg is better known. Dagerman’s blend of anguish and intellectualism has won him readers, particularly among young people who may be afraid of adult responsibility but seek an earnest discussion about the meaning of life. In France, some twenty famous authors have testified about their experiences reading Stig Dagerman’s novels, particularly A Burnt Child and Wedding Worries. He has been revived, not least through his dramas, also in Italy and Germany, where most of his work has been published. In the USA, a new translation of short stories, Sleet, was recently published and met with strong response.

From the start, Dagerman was a European witness. A poet and a reporter, a dramatist and not least a masterful author of Dagsedlar, daily poems published in the newspaper where he worked – bitingly ironic, always siding with the vulnerable. Eleven volumes of his collected writings appeared in Sweden in the 1980s and testify to the versatility and mastery of language. But also his despair, that so many have come to identify with as if it is of their own time. Dagerman worked across many fronts. A loner who sometimes was drawn to the glitter of high society; an eroticist in search of the mother who had given him up at birth.

He is a role model today because Dagerman was one of the few who stood for human rights, no matter which way the wind blew. Tirelessly attentive and fierce against dictators in the Eastern Bloc, rearmament and racism in the USA, Swedish compliance in the case of Raoul Wallenberg and the Catalina plane downed by the Russians. He stood up for the rights of the individual against the powers that be, for the tortured and imprisoned against a hangman’s pains of power.

The role of literature to him was to fight for the freedom of the individual and lay bare the meaning of freedom. He considered a State’s insistence on the subjugation of its citizens, whether on a greater or smaller scale, a deadly illness. This theme of the individual vs. the collective runs through his novel Island of the Doomed. Another theme he will return to, again and again, is the failure of honesty and disclosure as a road to empowerment and the possibilities of self-deception.

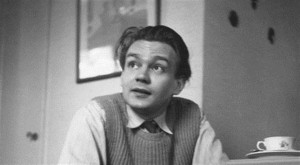

It is said that all great literature is about love and death. In Dagerman’s case: much death, little love. He bears the middle name of a drowned man. With absentee parents, he was raised by a beloved grandfather who was stabbed to death by a madman. His grandmother died of grief soon thereafter. His closest friend died in an accident. It seemed to him as if death and suffering was drawn to him. Anguish was his to inherit. Two things fill me with terror: the Executioner within me and the blade of the guillotine above me [from The Snake]. But there was also joy and tenderness, a hearty dose of humor and angry protestation against the abuse of power. Nearly seventy years ago, he was appointed Cultural Editor of The Worker, a daily that offered generous column space to young writers. I myself began writing there as a 17-year old and met Dagerman in the smoky corridors of the Klara Folkets Hus. He was a shy person, least of all opinionated, tolerant even, in the company of rich and poor alike, and humorous to boot. At dinner with publisher Carl Björkman, I watched Dagerman pick up the phone at 3 a.m., ever fascinated by the facility of technology, and call Sven Aurén in Paris. He was one of the authors signed by the publishing house and a reporter for radio and the daily Svenska Dagbladet. Aurén was awoken by Why aren’t you here, we miss you, and flew into a rage that he hadn’t been invited.

Dagerman has proven to be timeless in spite of his writing being peppered by markers of the 1940s: the ice-block melting in the hallway, the radio in the place of honor in the living-room, and the water streaming down the window of the fish store. Wedding Worries, his novel anchored in the farming society of a bygone era, sets the stage for a timeless play about guilt and death – inhabited by characters observed through the eyes of a child: magnified, grotesque, frightening. Like in a ballet, each take form in light reflected by others, and the novel’s famous raps on the window pane carry a message to them all – about another possible world, about duty and joy, about the friend for whom everywhere I seek. In short: about our need for consolation.

I heard Stig Dagerman read his poem Birgitta Suite at a high-school for girls at Bohusgatan in Stockholm. I have heard few people read as beautifully and gently. In this piece, he moved from anguish to longing, from fearfulness to becoming his own “key to freedom”, and here love is the answer to the question of freedom. Who knows what freedom is, Birgitta, if not the one whose love is boundless?

In 1943, when Dagerman was given an exemption to marry because he was under-age, he acquired two parents-in-law who were anti-Nazi Anarcho-Syndicalist activists and who miraculously had eluded the concentration camps. Annemarie Götze became a Swedish citizen through marriage, and that meant protection. Stig moved into the home of his parents-in-law where other refugees gathered, and that gave him a window onto Europe’s struggles and destruction. At the same time, in this home in working-class Stockholm, he rediscovered some of the calm assurance of his grandparents’ farm.

In November 1950, Stig Dagerman met actress Anita Björk and would live with her for four years. It was in their joint home that he struggled with what might have become a great work, that shimmering fragment: A Thousand Years With God. He wanted to be seen and heard, but still not reveal himself. He veiled himself but came to be seen with clearer clarity. Dagerman drills into a private well, an existential current springs forth, and from the darkness a robust vitality is unleashed. He speaks for those who are vulnerable and those who search for answers to eternal questions. It is among young people that he still has a majority of his readers.

Dagerman said that he was suffering from a chronic self-hatred, and an immutable predisposition that would harm others. He needed death like a tightrope walker his stabilizing stick. I only care about that which I never receive: confirmation that my words have touched the world’s heart [from Our Need for consolation Is Insatiable]. In uttermost solitude, space starts to sing. It is in the proximity of death that his prose becomes most urgent. Guilt, anxiety and fear run deep in most of his writing. In Dagerman’s work no one manages to establish real human contact. My lack of freedom is my fear of living. His friend, the poet Werner Aspenström, called him an unrealized death-mystic and felt that his service in the world was like a guilt-ridden apology for a secret longing for reconciliation beyond it. A dream of salvation without religious connotation: I beg for reconciliation and community but all I will receive is an aesthetic appraisal.

Still, it can be argued that freedom is the key word in his writing, and that a novel like Wedding Worries should be read primarily as an affirmation of the possibilities of individual freedom. Here, he is far from being a pessimist obsessed by angst, and instead someone who finds freedom in down-to-earth conscious pragmatism like make do with what you have.

Stig Dagerman once discussed his novel A Burnt Child at Stockholm University and outlined his manifesto: I believe in solidarity, compassion and love as the last white shirts of mankind. Above all other virtues, I hold a form of love called forgiveness. /…/ It is this goodness that exists in every human being that makes it possible for us to expect and provide consolation. [from Do We Believe In Mankind?]

And: One thing only is in your power: to treat a fellow human well. [from the poem A Brother Gained]

— Speech at the inauguration of Manuskript, sculpture by artist Lars Kleen to commemorate Stig Dagerman — Enebyberg, Stockholm, May 2014

Translation by Saskia Vogel and Lo Dagerman